The BELA Bill is the Basic Education Laws Amendment Bill, and is an attempt to make amendments to the South African Schools Act (SASA) of 1996.

The Department of Basic Education (DBE) claims that the BELA Bill seeks to align the SASA to the other existing laws of South Africa, and that they will ensure that the BELA Bill is transformative and promotes social cohesion.

However, although these sound like noble ideals, the BELA Bill does not, in its current form, address the inherent challenges in education, and all it really seems to achieve is to strengthen the administrative capacity of the Minister of Basic Education to make broad policy decisions.

The Bill has been in the spotlight since October 2017, when the DBE first published the amendments for public comment.

On Sunday, 1 October 2023, the DBE held a press briefing in which Minister Angie Motshekga announced that the BELA Bill, S‑List had been adopted, and that after ten years of working on it and consulting with all the stakeholders it would imminently become law.

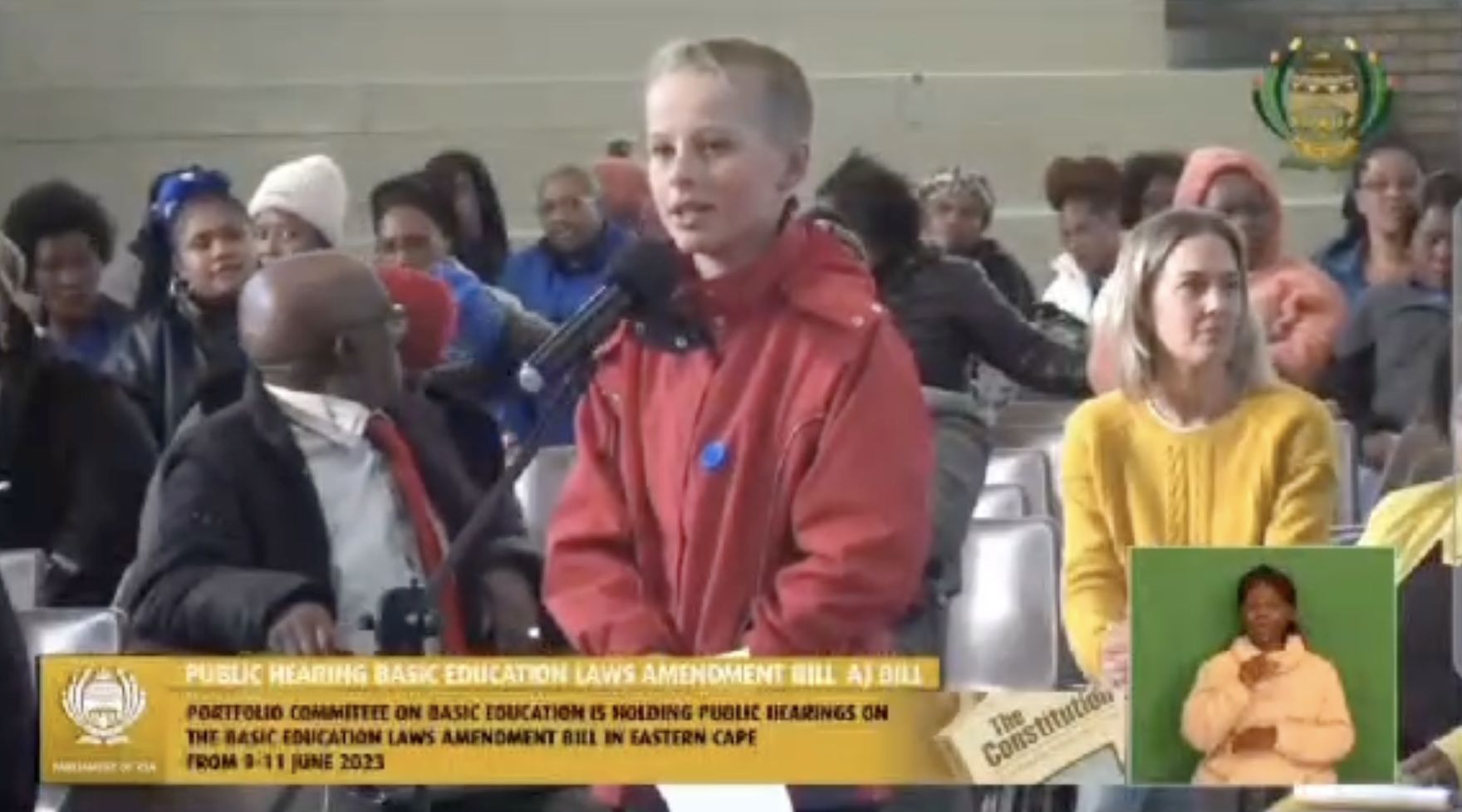

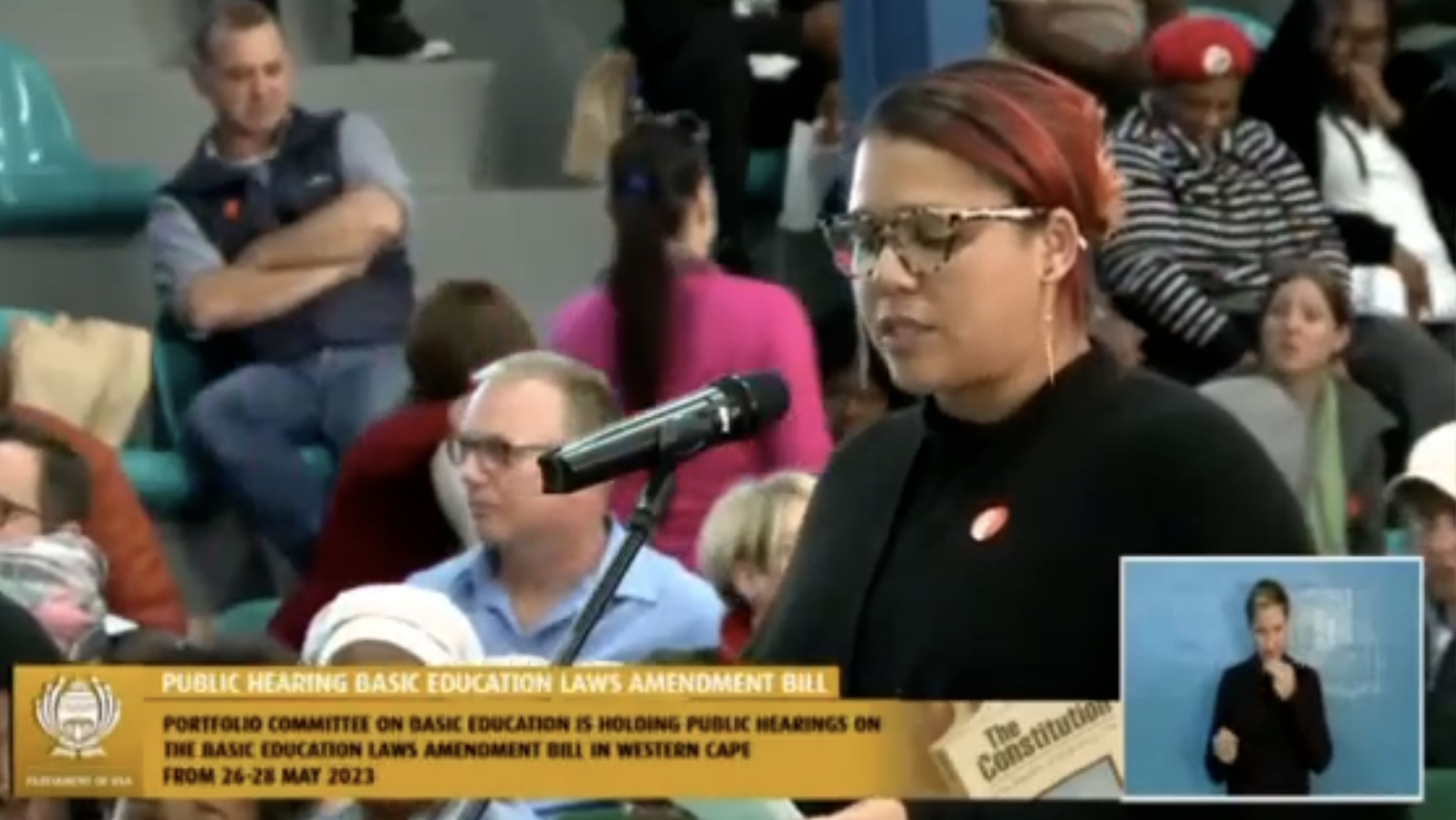

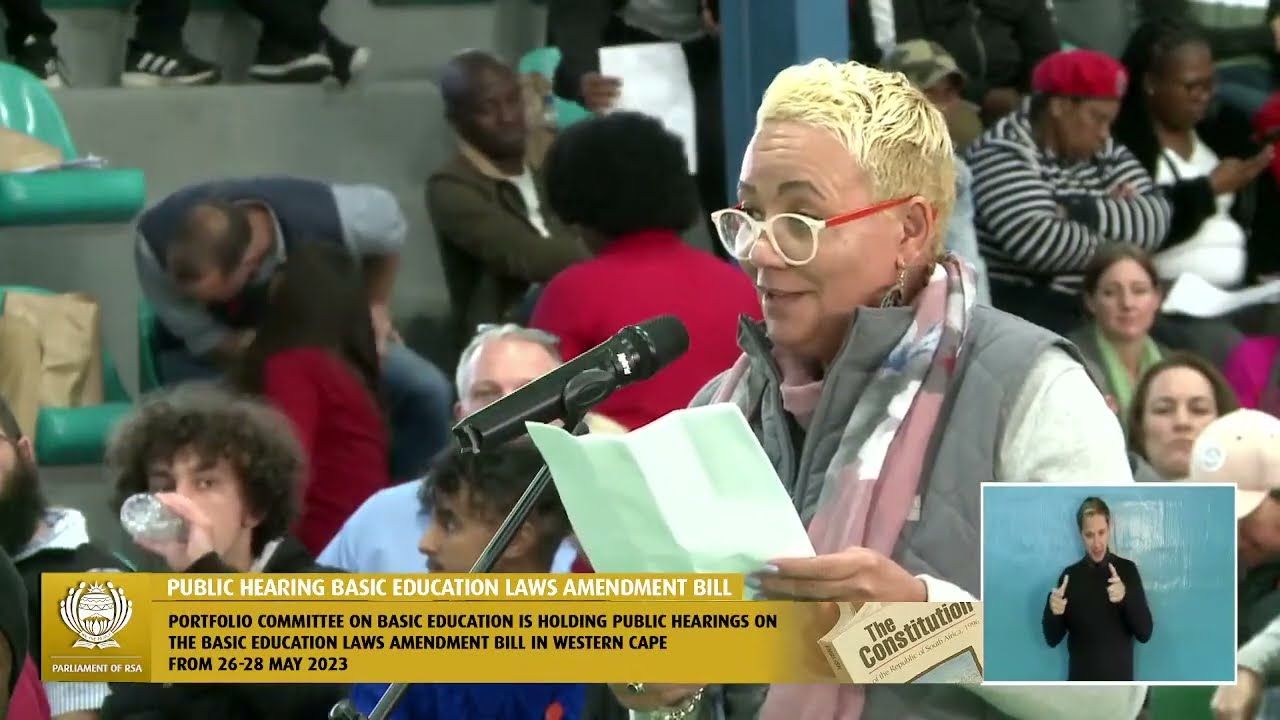

Many who participated in the Public Participation Process including written submissions and attending the Public Participation Hearings feel that the views of the public are not adequately reflected in the current version.

It is important to note that the BELA Bill is not yet written into law.

The Bill must still be deliberated at the National Assembly as well as in The Council of Provinces. During this process, there might be another possibility for public participation.

It is the right of every single parent to be able to decide what is the most suitable and ideal educational route for their child. Nobody understands the educational needs of children better than their own parents. This is a principle that must be steadfastly defended and respected, yet the government seems unwilling or unprepared to accept this, and thinks they have a monopoly on how our children are educated.

In the home education community, the contentious problem of the BELA Bill is not a new one. Families new to home education that have entered the playing field due to the COVID-19 pandemic over the past few years have come to see that home education legislation is not supportive, and if the BELA Bill is passed as law in its current form, thousands of home educating families’ choices will be severely impacted.

This proposed Bill is the first major revision of the post-Apartheid education landscape and will likely shape that landscape for the next 10 to 15 years.

If you have a child in school or who will be starting school in that period, the BELA Bill will impact you. South Africa’s public basic education system is one of the most dysfunctional in the world. Taking more power away from parents and placing that power in this system is misguided, irresponsible and quite frankly, a disservice to our country’s youth.

Sadly, given what the vast majority of South Africans currently experience on a daily basis, there is no reason why parents or guardians would allow any legislation that would extend control of their children’s education and limit their alternatives and options. Government needs to earn our trust and justify any measures or legislation they put in place.

The rights and well-being of children must be protected. However, parents and guardians of South African children need proper information pertaining to the legal framework of any proposed legislation.

One of the major concerns with regard to the BELA Bill is that it grants open-ended powers to government without proper definitions, references and detail describing the method in which the proposed regulations will be enforced.

What protocol would permit a school inspector to demand access to a private home in order to inspect how a child is being educated there? What parameters would be used to assess and oversee that home-school? Taking into account that an inspector visiting such a home may not even be able to discern whether education is taking place there. This stipulation in the Bill proposes that a private home is an extension of the formal school system where an inspector would have a mandate to inspect it.

So this is just one example why home education, for example, cannot be covered by a simple clause added to the South African Schools Act. Yet, that is exactly what the BELA Bill proposes. Clause 37 35, on home education, seeks to restrict curriculum choice for home schoolers and subject them to much closer monitoring and regulation. Home schoolers are, therefore, opposing this vigorously and have been the most vocal and organized opponents of the Bill. It is most probably testament to their political acumen that much of the coverage that the Bill has received has been about home-education. It is also the reason that many parents in the general school community think of the Bill as a home-education bill.

The Bill will, however, significantly reshape the education landscape, not just for the roughly 50,000 home- schoolers, but also for the more than 12-million learners in public schools across the country.

Some of the other key areas of concern are regulations that will affect school governing bodies, admissions and language policy, provision for the sale of alcohol (clause has been removed), no provisions for alternative curricula, legislation of Grade R as the starting age and much more (more details about this in the sections that follow).

All in all, the BELA Bill should be discarded, and two separate Bills drafted: one to cover the changes to the South African Schools Act, and another to address Home Education as well as all other modalities of education that have sprung up over the past three years and which have not been brought into consideration by the BELA Bill.